The power of The Lord of the Rings as a story is strongly tied to the concepts of fate and free will, raising the question of whether someone is truly responsible for their actions. The story revolves around the tension between a sympathetic kindness that sometimes seems inherent to Middle-earth and the danger, uncertainty, and seeming hopelessness of the path ahead. This tension creates the drama and suspense that make the story tragic and sets up what Tolkien coined as eucatastrophe – the last-minute aversion to a seemingly inevitable catastrophe. The Eucatastrophe occurred when the Great Eagles arrived, out of nowhere, to rescue Frodo and Sam from the slopes of Mordor’s Mount Doom.

If it was always clear to readers that all of history’s disasters were meant to happen and were ultimately good, even though great travesties were not possible due to a divine plan, some of the wind would be taken out of history’s sails. In many ways, the nature of destiny and free will becomes painfully clear The Lord of the Rings for those who pay attention. But these topics are philosophically challenging, so their debate in LOTR fandom is understandable. Furthermore, a bit of ambiguity about the destination in Lord of the Rings‘Middle-earth is part of what makes romance nail-biting.

The Lord of the Rings has a God called Eru Ilúvatar and Eru has a plan

Destiny exists in Lord of the Rings

Fate and free will in Middle Earth are heavily contested by The Lord of the Rings fandom, and this entire discussion revolves around One Eru Ilúvatar. Eru is the God of Middle Earth, inspired by the Catholic God of LOTR creator JRR Tolkien. Tolkien confirmed that LOTR was not a Christian allegoryand he criticized his friend, C.S. Lewis, for creating such a blatant Christian allegory in The Chronicles of Narnia. But he confirmed that there were allegorical elements LOTR. Eru is referenced in The Lord of the Ringsmore explicitly in the appendices, where it is called “the One.“

Consequently, Eru is not mentioned in Peter Jackson’s book Hobbit and Lord of the Rings trilogies. But The Silmarillion revealed Eru in all her glory, clarifying what was suggested in Lord of the Rings. Eru enacts divine providence in Middle-earth, as confirmed by Gandalf, Tom Bombadil, and Elrond in LOTRdiscussing how chance encounters and coincidences are actually “something else at work.“ Fate is the manifestation of divine providence in the world, while chance is how divine providence appears to those who do not understand the plan. Tolkien scholar Kathleen Dubs first vocalized this idea.

Eru gave his subjects free will in The Lord of the Rings, making them responsible

Free will exists in Lord of the Rings

Despite fate, everyone in Middle Earth has free will. In his letters, Tolkien confirmed Eru as “never absent and never named,“controlling the events of Middle Earth to such an extent that it is”The Other Power“what”then took over” in the Cracks of Doom, guaranteeing Gollum’s fall into the lava. And yet, Tolkien also confirmed in a letter that Elves and Men “they were rational creatures with free will in relation to God.“ It certainly seems that way, since Lord of the Rings. Gandalf, possibly the closest thing the novel offers to a divine agent in Middle-earth, was not blessed with complete certainty and confidence.

In The SilmarillionEru criticized Morgoth for going against his wishes, suggesting Morgoth’s guilt in the matter. A close reading of the legendarium demands the conclusion of both fate and free will operating in Middle-earth. Being modeled after Tolkien’s Catholic God, Eru is benevolent. If Eru is benevolent and executor of divine providence and fate in Middle-earth, the ancient question of the origin of evil arises here with the same certainty as it does in the real world. But if free will is in effect, then any of Eru’s life forms could choose to instigate evil in Middle-earth and be all responsible for their actions.

Although it’s mind-bending, free will and destiny are compatible in The Lord of the Rings

Characters subject to Eru’s plan also have free will in The Lord of the Rings

It seems strange that free will is possible in a world subject to God’s plan, but destiny and God’s plan coexist in Middle-earth. Lord of the Rings powerfully suggests that Middle Earth is not deterministicand indeed it is not, which is the key to its danger and beauty. Tolkien scholars as diverse as Kathleen Dubs, Corey Olsen, and Tom Shippey agree that the Roman philosopher Boethius strongly influenced Tolkien, and Boethius explained how fate and free will coexist. Eru lives outside of time, as Boethius claimed God lived. So nothing is pre-ordained. There is only one constant unity of each will.

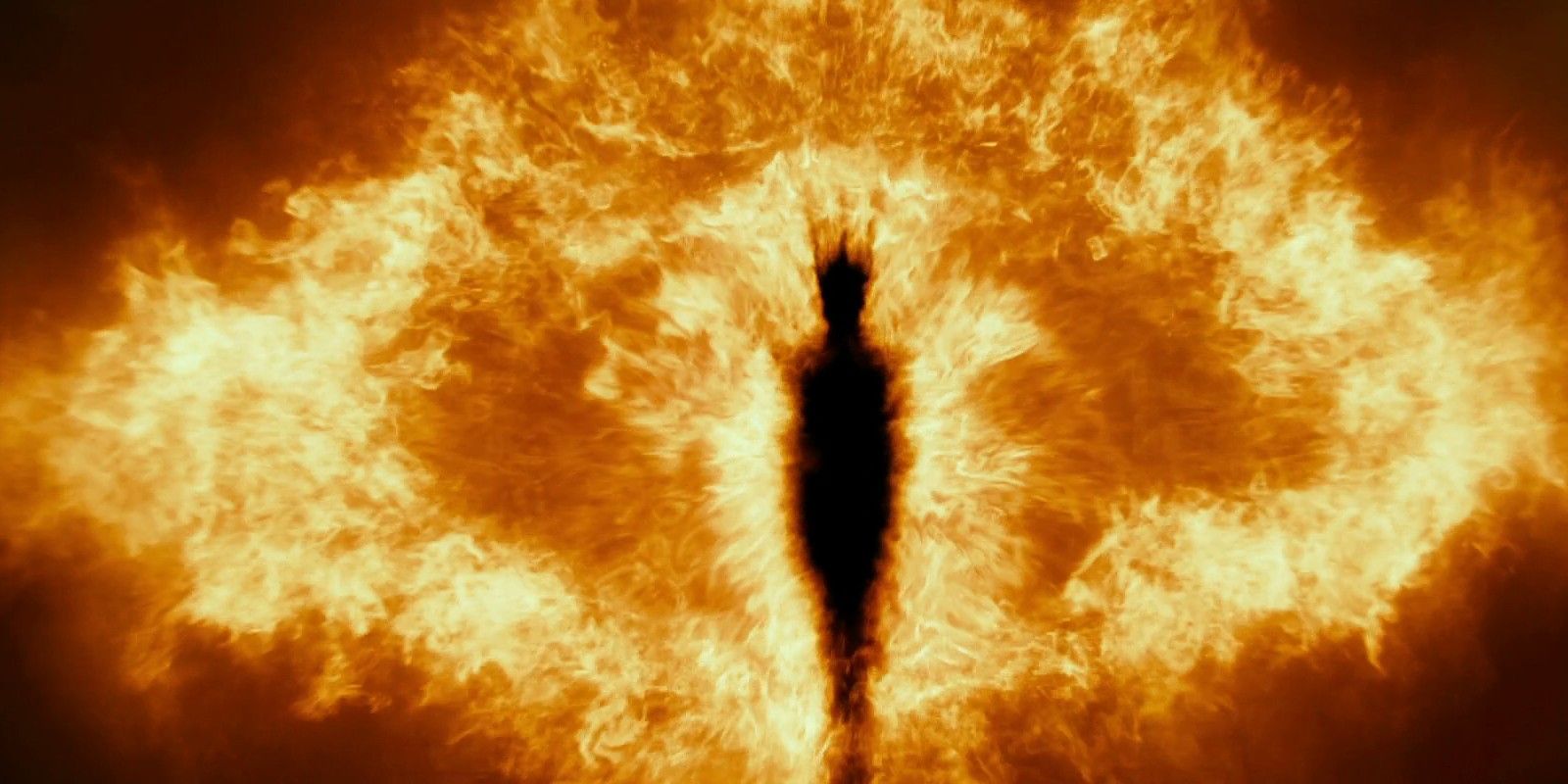

This might just be a radical, idealistic thing of great beauty. Boethius defended these views in The consolation of philosophywhich he wrote in prison after being accused of treason, magic and sacrilege, and before being executed in a torturous manner. Perhaps the truly new can only be forged in fire; Sauron could testify. Middle Earth was the world Tolkien wantedand by firmly distancing it from allegory, he ensured that his use of Boethius’s vision was freed from the complexities of real-world religion. Although inspired by a Christian writer, the fate of Middle-earth carries a powerful message for everyone: strive and hope.

Eru is benevolent, but subcreation can introduce evil into Lord of the Rings

Eru did not introduce evil into Lord of the Rings

Examining fate and free will in Middle-earth confirms that both exist, allowing for the introduction of external evil to a benevolent God, but Tolkien approached the origin of evil in Middle-earth in terms of creation and sub-creation. As the One creator, only Eru had the ability to bestow life, the Imperishable Flame. True creation was akin to divinity, for no act was as divine as creation. Creation by any other being was a sub-creation. As such, creative acts, increasingly, as they moved away from Eru, were vulnerable to pride and arrogance.

The fate of Middle Earth has a powerful message for everyone: strive and hope.

The Valar subcreated nature in Arda, but Saruman subcreated its war engines from nature, making them more vulnerable to corruption. Before Arda began, Vala Morgoth, the original villain of Middle-earth, left his place in the Timeless Halls with Eru and the other Ainur to search for the Imperishable Flame in the Void. Morgoth’s desire to create life foreshadowed his desire to become God. In a letter, Tolkien described Morgoth as “the Subcreative Rebel Prime.“ The Vala Aulë also rebelliously sought to come to life, but apologized when discovered, avoiding the “ruinous path“that Sauron followed Morgoth. Tolkien confirmed that”It’s… introduced subcreatively… badly.“

Before Arda began, Eru led the Ainur in the Ainulindalë, a song that partially visualized Arda and its history. Men in Middle Earth had “a virtue to shape their lives, amid the powers and opportunities of the world, beyond the Music of the Ainur, which is the destiny of all other things,” confirming that Men had a certain degree of exemption from providence. But all species of Eru in The Lord of the Rings were subject to a level of provision. From Eru’s place outside of time, he constantly worked toward a greater good than anyone trapped within the linear boundaries of time could comprehend.